“Boxing is particularly precious, and there are few spectacles as wholesome and delightful as a boxing match.” These are the phrases of a 26-year-old Vladimir Nabokov, taken from a paper he delivered to a Russian émigré literary membership in Berlin in 1925. In it, the long run titan of twentieth century literature and creator of Lolita and Pale Fireplace expounds on his idea of boxing as a redemptive expertise by which bodily magnificence is created by the collision of opposing fighters. For the younger creator, the extemporaneous nature of video games and sports activities was the supreme method for a person to precise his vitality. Boxing, with its incomparable synergy of physicality and mind, supplied Nabokov with a singular visceral expertise.

The paper is titled ‘Breitensträter – Paolino,’ and experiences on a heavyweight struggle held between a well-known Basque, Paolino Uzcudun, and the German boxer Hans Breitensträter. Revealed for the primary time in English within the Instances Literary Complement in 2012, the piece begins with a brief treatise on the liberating nature of video games. For Nabokov, play was ‘every thing good in life,’ whether or not the train was psychological or bodily, and undertaken by artwork or athletics. Superior to the unthinking rigidity of army train, aggressive sports activities like boxing had been particularly invigorating, as they supplied males with a artistic method to have interaction their bodily instincts. No stranger to the ring, Nabokov as soon as boxed himself, and it’s clear the game held appreciable sway over his younger creativeness.

On this quick essay, he writes knowledgeably a few still-youthful sport. He takes observe of Jack Johnson’s epoch-making victory over Jim Jeffries, saying that in retirement Johnson “rested on his laurels, gained weight, took a fantastic white lady for his spouse, started showing as a dwelling commercial on the music-hall stage, after which, I believe, ended up in jail, and solely briefly did his black face and white smile flash out from the illustrated magazines.” He describes having seen Bombardier Wells, ‘the miraculous Carpentier,’ and likens Canadian Tommy Burns to a ‘London Dandy.’ Nabokov is writing about boxing in arguably its biggest period, and invoking the fighters whose deeds ensured the heavyweight title would typify the hyper-masculinity that so enthralls the author.

To buttress his credentials as an appropriate voice for the game, Nabokov assures the reader that being knocked unconscious is surprisingly agreeable. He claims that in a dangerous punch “which brings on an instantaneous black-out, there’s nothing grave. Quite the opposite, I’ve skilled it myself, and may attest that such a sleep is moderately nice.” I can personally attest that there’s some fact right here, however the lack of consciousness is extra banal than satisfying, and finally turns into scary when one’s bruised mind registers the injury it’s sustained. Right here, Nabokov is writing with vainglorious glee. He did field at Cambridge (an expertise he describes in his peerless autobiography Communicate Reminiscence), however I’ve problem believing {that a} man as terribly clever and delicate as he, nonetheless younger and inexperienced, might have been so flippant in regards to the well being of his most beneficial organ.

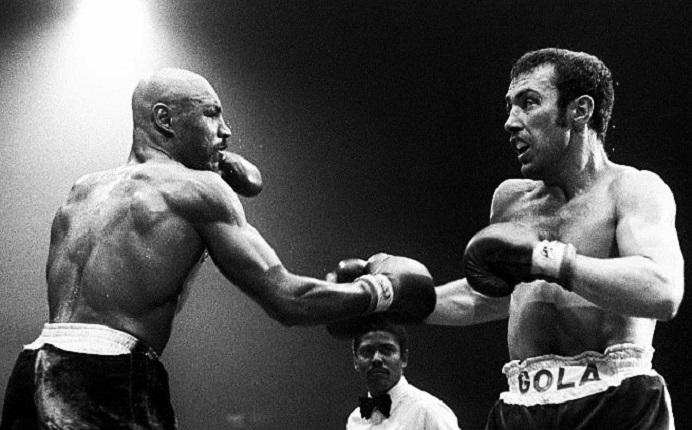

Nabokov’s description of the 1925 bout between Breitensträter and Paolino in Schöeneberg, a borough of Berlin, is a effective one, and appropriately verbose. “Across the luminous dice” he writes, “throughout which the boxers danced with the referee twisting between them, the black darkness froze, and within the silence the glove, shiny with sweat, slapped juicily towards the stay bare physique.” Paolino, who took on the best heavyweights of his day, together with Max Schmeling and Joe Louis, knocked the besieged German out in spherical 9. “In a frenzy and discord, the darkness roared. Breitensträter lay twisted like a pretzel. The referee counted down the fateful seconds. Nonetheless he lay.”

‘Breitensträter – Paolino’ is an attention-grabbing and worthwhile piece for devotees of Nabokov’s fiction and anybody fascinated about boxing. Initially written in Russian, the interpretation, which Thomas Karshan mentioned was undertaken with the concept of retaining the nuances of the younger Nabokov’s prose, is nicely achieved, but it surely elicits not one of the charming rhythms that distinguish later masterpieces like Lolita and Pale Fireplace as towering monuments to the vary and fantastic thing about the English language. Nonetheless, any look of ‘new’ Vladimir Nabokov is noteworthy for an English viewers and Karshan and the conspicuously-named Tolstoy must be counseled for producing a full of life translation.

As if talking on to the boxing obsessed literati he references earlier within the piece—notably his beloved Pushkin—Nabokov ends the piece with a protracted, idealized dissertation on the virtues of institutionalized violence. Opposite to his idea, boxing isn’t, because the adage maintains, one thing that one ‘performs,’ however there’s fact right here in his description of the uncommon emotion it invokes in its followers:

And so the match got here to an finish, and once we had all emptied out onto the road, into the frosty blueness of a snowy evening, I used to be sure, that within the flabbiest household man, within the humblest youth, within the souls and muscle tissue of all the group, which tomorrow, early within the morning would disperse to places of work, to retailers, to factories, there existed one and the identical lovely feeling, for the sake of which it was price bringing collectively two nice boxers, — a sense of dauntless, flaring power, vitality, manliness, impressed by the play in boxing. And this playful feeling is, maybe, extra precious and purer than many so-called “elevated pleasures.” — Eliott McCormick